In this article which was originally published in the September 2023 issue of BATOD Magazine, Ken Carter provides a brief overview of the latest research study based on experiences of students in higher education. This article is based on the Findings and Recommendations sections of the project blog, as well as the Project Final Report (Graham, 2022: Final Report: Access and Higher Education: Inclusive Online Learning for Deaf Students).

Introduction

This project, generously funded by the Leverhulme Trust, set out to focus on how best to support higher education (HE) students who were deaf or hard of hearing (DHH), dyslexic (DYS), or who had English as a second or other language (L2).

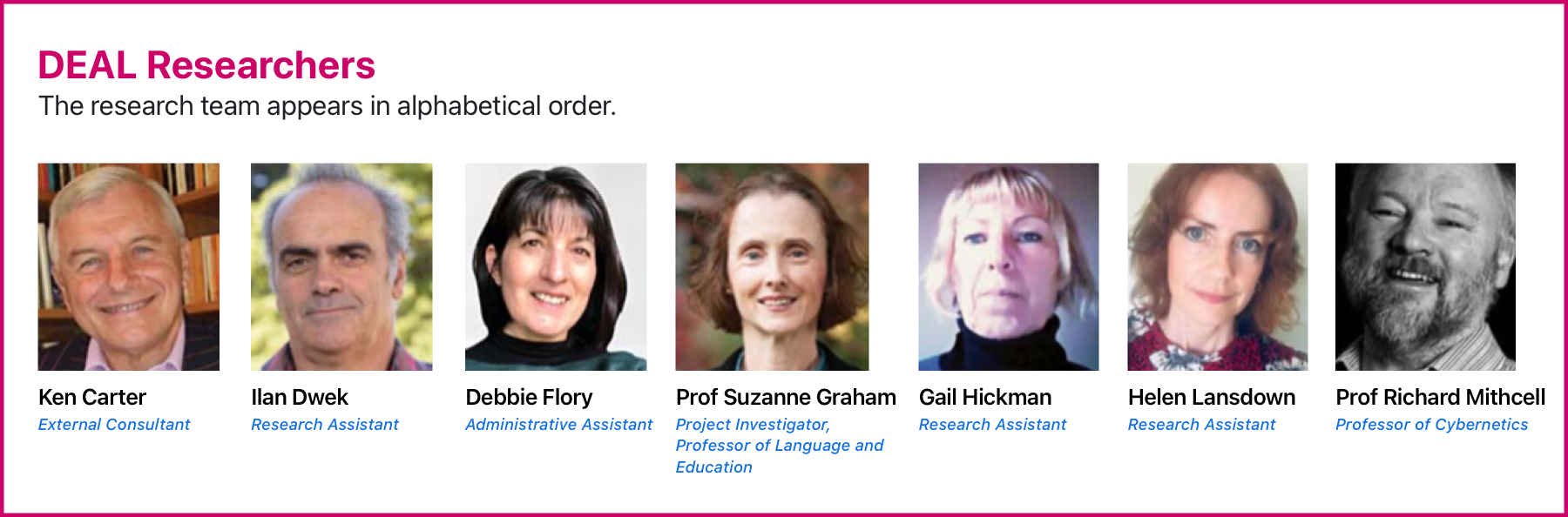

This interdisciplinary, collaborative project brought together colleagues from the Institute of Education, University of Reading, who were experts in promoting good teaching practices and had a strong portfolio in research on the barriers to learning for students with disabilities and special needs, with colleagues from the Department of Computer Science with programming expertise in online learning. They were joined by high-ranking members from Deafax, AACT, and GOALS4LIFE charitable enterprises. These charitable enterprises wanted to ensure this important project was well grounded in users’ experiences. The Institute of Education is well-known for its research in language and literacy, with current research in reading, vocabulary acquisition, bilingualism, and English as a second or additional language.

Digital access for Deaf people has benefitted from the development of automatic speech recognition (ASR), but its accuracy varies with context. Mistakes made through ASR are less confusing if you have good literacy and can guess, on the basis of phonetics, what the substituted word should have been. Both aspects are more likely to be problematic for the deaf learner. However, research suggests that signing is not necessarily a better medium than text, especially for acquiring new technical vocabulary. Text can be static, read, and re-read for meaning. A central debate concerns whether it should be provided word for word as spoken or whether it should be edited, and if so, how. Paraphrasing can result in text that is dense and harder to mentally process, with too much information in too short a time. Our research concerned examining the linguistic and cognitive demands of text and testing modifications. In addition, deaf learners were found to benefit from a variety of visual aids. The challenge was to understand how they could best be accessed online in a manner that does not overly divide attention and prove distracting.

Although the prime focus was on DHH learners, research suggests that other students with literacy and language difficulties also benefit from subtitling and visual materials. These include those who were neurodiverse, particularly those with DYS, and those who spoke L2, and therefore there was much also to be gained from examining how these other two groups benefitted.

Study Online

Members of the research team recruited participants through calls to universities and to organisations supporting adults who were DHH, are neurodiverse, particularly for DYS, or speak L2. We created two versions of online learning materials across two content areas using University of Reading materials on FutureLearn Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC): ‘Begin robotics’, and ‘Understanding anxiety, depression and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)’. These were a mixture of online written texts and video clips. The latter included both ‘talking head’ type material and PowerPoint slides with voice-over. One version of the materials was ‘unenhanced’ – in other words, it appeared in exactly the same way as it did in MOOC on FutureLearn. We called this version MOOC. The other version was ‘enhanced’, that is, modified to try to offer greater support to those in our three participant groups. We called this version DEAL.

The main modificatinos included:

- adding Advance Organisers (signposts given to students before they undertake an activity to help them structure the information they are about to learn and to direct their attention to key points):

- pre-viewing explanations of difficult vocabulary

- breaking down some of the information into smaller segments with summaries

- adding British Sign Language (BSL) to video clips

- drawing participants’ attention to how to modify and use captions.

Although captions were available in both versions, with on/off and speed control, these features were not explicitly highlighted to the MOOC group. By contrast, they were highlighted in a pre-viewing document for the DEAL group. Participants were randomly allocated to either the MOOC or the DEAL condition, across all three participant groups.

Procedures

Information was gathered from participants regarding their proficiency in reading English and their existing knowledge of robotics and CBT-related topics. Participants then met online with a member of the Project Team and viewed one version of the two sets of online materials. After viewing, they completed quizzes to assess what they had learnt, and also a questionnaire and interview to find out what they had focused on while viewing, and what they had found helpful and unhelpful. A sub-sample of participants had their eye movements tracked as they viewed the robotics materials.

Summary of findings

Learning – was the MOOC or DEAL version better for helping participants learn the online content?

For both the CBT and robotics materials, taking into account participants’ reading proficiency and pre-viewing knowledge, after viewing the materials, the scores for both MOOC and DEAL were very similar. The only statistically significant difference was for the L2 group, who performed worse after viewing the DEAL materials for CBT.

On the more complex robotics materials, the DHH DEAL participants had higher average scores than DHH MOOC participants. This gives some further indication that the DEAL modifications helped the DHH participants. Similarly, although overall DHH quiz scores were the lowest of the three participant groups, they only did worse than the other two groups when they viewed the MOOC version, giving indications that the DEAL version had some equalising effect on learning.

What did participants think about the presentation of the online content?

Across all three groups of participants, modifications made in the DEAL versions of materials were found helpful in respect of the tasks that accompanied the videos, the texts that introduced the videos, and bullet points/summaries of key learning points. These features received more positive ratings in the DEAL version than in the MOOC version.

There were, however, a lot of individual variations in respect of what was helpful and what was not. Several participants expressed the desire to be able to personalise their viewing: for example, to be able to move the captions or the BSL to a certain area of the screen. This was reflected in the large amount of variation regarding the areas of the videos they looked at, which we captured using eye tracking software. Many DHH participants found having BSL and captions hard to process together. The overriding message for online learning is that one size does not fit all, and personalisation of modifications is key.

Our recommendations

The DEAL research initiative has developed guidelines aimed at improving online provision of teaching and learning content. It has focused on students who are DHH, those who are neurodiverse, especially those who have DYS, and those who have English as a Second or Other Language.

Our research explored the experiences of students and recorded their views, making it possible for us to better evaluate current online practices.

Our recommendations are of particular relevance to practitioners in HE and aim to improve the student experience when learning online. They are taken from our study findings that point to what aided students’ understanding and learning when viewing online materials.

Our recommendations and accompanying examples are divided into three overlapping categories as listed:

- Preparing teaching and learning materials in a HE setting? Then visit the section for Lecturers, Educators, and Practitioners.

- Looking for guidance on ways to present your content? Visit the Presentation section.

- Looking for guidance on a more technical front? Visit the section providing Technical Pointers. Please note that BSL translations have been added to all pages on the DEAL website https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/deal/researchers/

This article was originally published in the September 2023 issue of BATOD Magazine